All environment photos by Tom LaFaver

*text from SPACES archives

Ida was one of ten children born to a family that generations earlier had immigrated to the United States from Germany, settling in the ethnic German communities around Schulenburg, Texas. Her mother died when she was young, and her father, unable to cope with raising his large brood, placed his children with a number of different relatives. Ida ended up with the Haas family of La Grange, Texas and, as a young woman, worked in town as a waitress. In her twenties, she moved to nearby Pasadena, Texas, becoming the live-in housekeeper and caretaker of affluent Robert Kingsbury’s terminally ill wife and their two teenage daughters. Two years after the first Mrs. Kingsbury died, Ida married Robert, a brazen act that scandalized the community and so shocked and offended the two daughters that they immediately left home, although they were still only in their late teens.

Somewhat isolated and shunned among the townspeople, Ida kept to herself and took pride in her beautiful house, filled with her collections of dolls and porcelain figurines and gracious furniture. She and Robert led a happily married life for thirty years, although it is said that they never referred to each other by their given names when in public, but only as Mr. and Mrs.

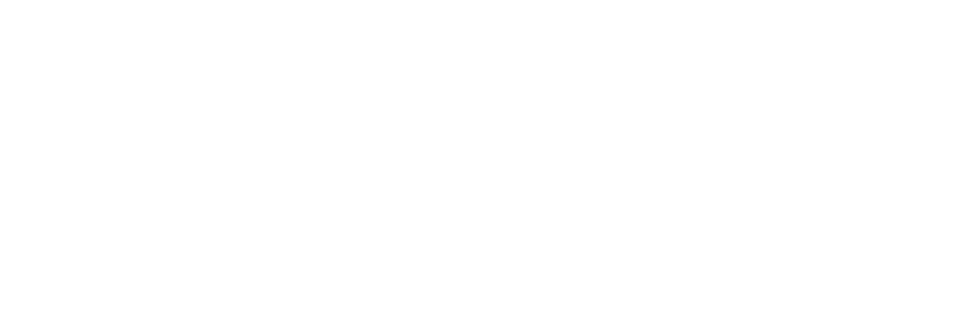

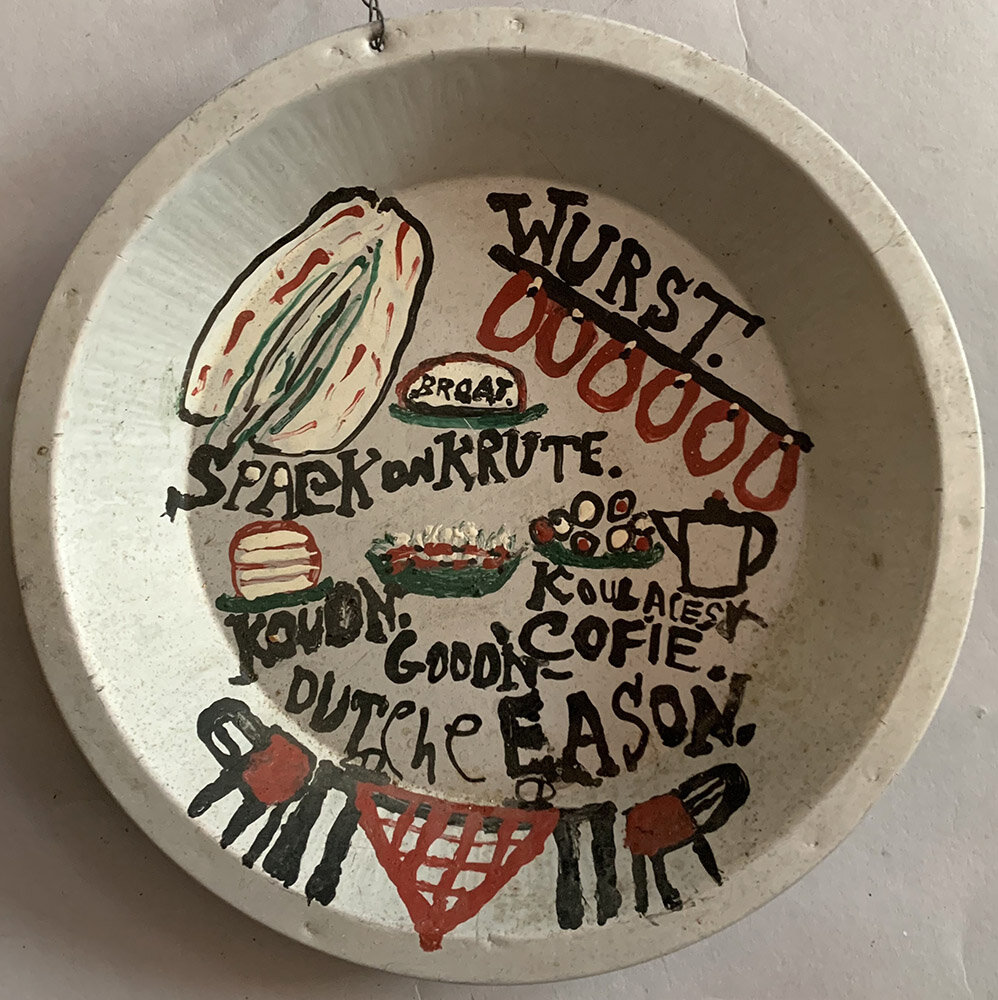

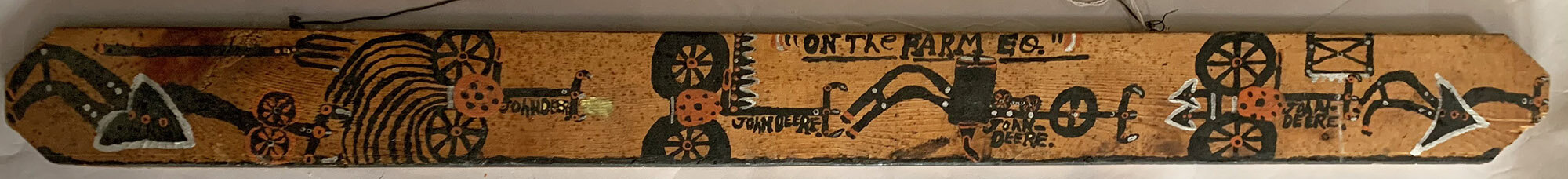

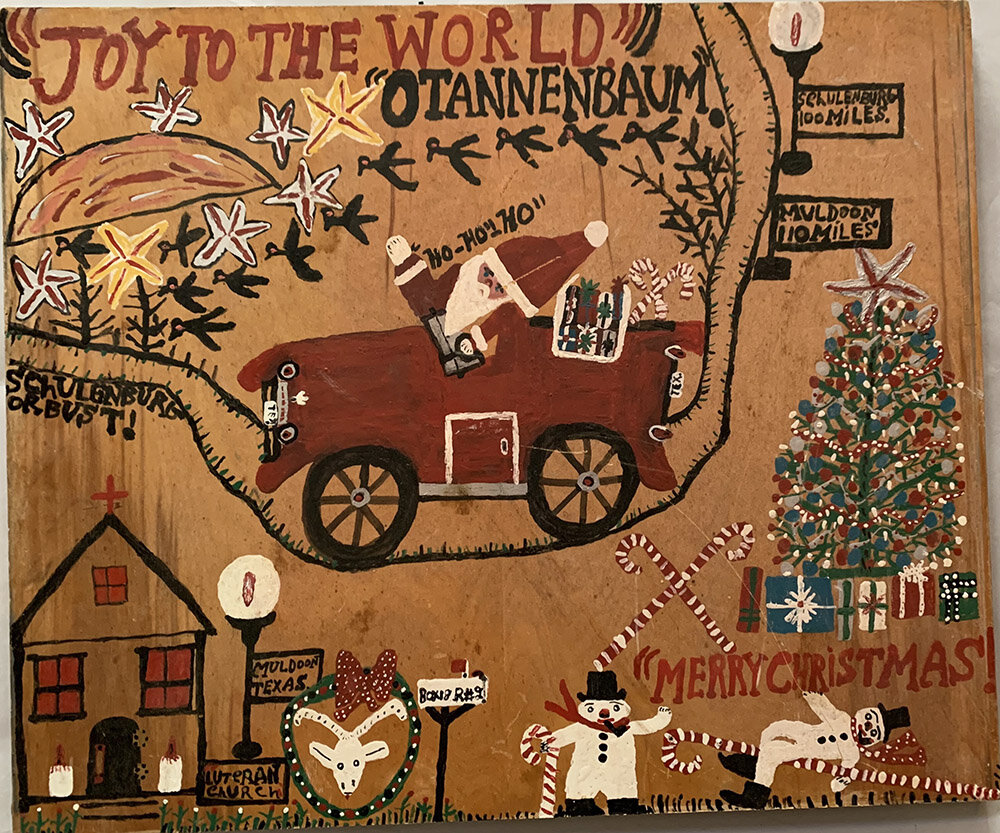

After Robert’s death in 1971, Ida began to collect more heavily, an obsessive activity that bordered on hoarding: after her death the entire house was found stacked, floor to ceiling, with piles of figurines, new and used clothes, furniture, fabric, papers, and dolls; in fact, it is said that in her later years she slept in her car because there was no longer room for her in the house itself. (It ultimately took more than a week of eight- to ten-hour days and a full-time crew of forty volunteers to empty the small frame house.) Her compilations soon spilled out from the increasingly overcrowded house to the surrounding yard. Working steadily until her death in 1989, she “planted” painted signs (such as “Those who are peacemakers will plant seeds of peace and reap a harvest of goodness,” “Home Sweet Home,” and “Bunny Boulevard”) alongside assemblages of found objects that she creatively and often humorously formed into anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures: she called them her friends and her pets, perhaps as a substitute for the lack of real friends that she suffered as a result of being ostracized by the townspeople.

It is estimated that Kingsbury may have assembled or modified and installed one thousand figures around her house and yard over the 18-year period of her active artmaking, including numerous ducks and some one hundred cats, cutouts from a variety of materials and each bearing a painted placard that read, “I hate cats.” Inner tubes, fence posts. roofing materials, hubcaps, concrete garden ornaments, ice trays, anchors, washboards and more were turned into idiosyncratic figures as well as those representing more iconic characters: cowboys, policemen, farmers, Uncle Sam, Old MacDonald. She used house paint and aerosol cans, and sawed and hammered and nailed as she saved everything and turned everything into an ornament. It became one of the most extensive and impressive art environments of Texas.

In February 1989 she was found, after several days, in the driveway of her home, dead of an apparent heart attack. The property was left to the stepdaughters, but the contents were left to one of Ida’s relatives. The relatives entered the house and smashed the dolls and figurines to pieces, mistakenly assuming that a fortune was hidden away within. And the stepdaughters rejoiced at her death, and refused to share reminiscences or photographs of the artist, claiming that she had forced them out of their home at a tender age. But a local group of supporters, including many who were involved in the preservation of the Orange Show in Houston, banded together to form the Friends of Ida Kingsbury, and raised money to offer to the family. The stepdaughters steadfastly rejected any contact with the Friends group, however, even refusing to take their phone calls. Roughly six months later, members of the group serendipitously visited the house to determine how they could best document it despite not having the stepdaughters’ permission, when they found a salvage crew ripping up the works and tossing them in a pile for destruction. They were able to make an emergency deal with the crew over the objections of the stepdaughters: the Friends would work to remove the artworks and clean up the site if they could retain the sculptures. Within hours a crew of volunteers had assembled, and they were able to save hundreds of pieces within an eight-hour time frame, transporting them to the garage for temporary safekeeping.

After being stored for years with many plans and hopes of where they would go, we stepped up 20 years back to carry the torch. We hosted an initial exhibit with hundreds across the walls of the gallery giving the sense of the huge environment. Finally, in 2005 about two hundred objects became part of the permanent collection of the Grassroots Art Center in Lucas, Kansas, its first acquisition of work by an artist from another state.

These pieces are so joyful and it is a beautiful yet sad story of Ida Kingsbury working so hard to keep and create her joy by making her friends around her, even behind a fence of chain link and emotional isolation.